Jazz and Other Mixed Metaphors

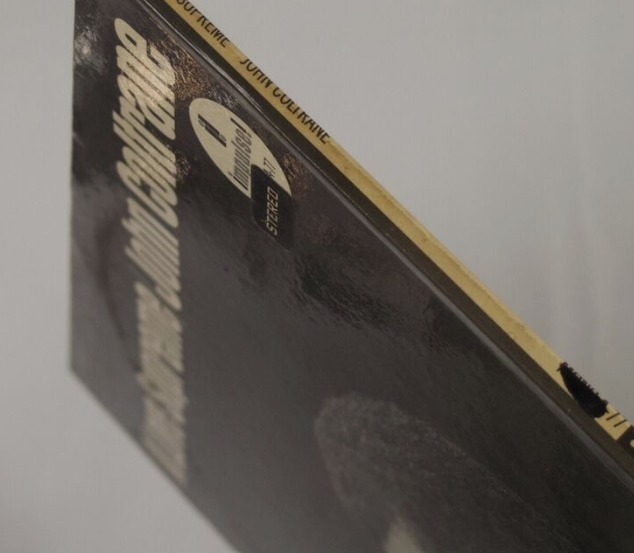

... That was eleven years later, to the day. Mason looked down at the light jitterbugging off of his Omega DeVille wristwatch. It was 22:59. The numbers on his spreadsheets finally confessed who their daddy was and he shut his computer down. With 250 milligrams of caffeine still coursing through his bloodstream, he grabbed a magazine and turned on the radio. A Love Supreme was playing start to finish on the public station. He remembered how in college he would often stow away on the Coltrane when it came time to wind down. Mason knew jazz back in those days—a vestige from Uncle Rick on his mother’s side, a smooth heavy equipment operator if he ever knew one. The 20-year-old Mason would say things like: “A Love Supreme is a subtle departure from the dense harmonic post-bebop of John’s earlier work.” No one knew what he was talking about, or cared. But he did. He believed a jazz song to be the ultimate trip— one that never stopped at the same corner twice and always ended up on the wrong side of town at just the right time.

But that was then. The 32-year old Mason didn’t listen to much jazz. Occasional background music maybe. Too meandering, per his new paradigm. If jazz were a person, he’d be holding up an excessively decorated cardboard sign under the overpass. Mason turned the radio dial and found the city news station. He caught the tail end of the business report, which played at :22 and :52 every hour. But these people didn’t know what they’re talking about, he decided. So he turned off the radio and reached for a cigar.

Just then, at 23:29, a text came in from his father: “got it! rosemont in our pocket. maybe you got a little of the old man in you after all”.

“Yesss!” Mason exclaimed, fist-bumping the air. The Rosemont deal was The Big One. More commas than a Hemingway sentence, he would tell himself. He immediately called Rachel, not concerned that it was nearly midnight. After ten or so rings she picked up. He didn’t wait for her hello. “Raych, whatever you have planned for tomorrow night, cancel it. Be here at 7:00. Don’t worry about finding an outfit—I’ll have one waiting for you.”

He knew she had on her “whatchu talkin’ ‘bout” face. But she didn’t ask questions. For one, she was half asleep. But more than that she loved surprises— especially from Mason, who was about as spontaneous as her monthly cycle.

“Good-bye, darling,” she said— her first and second, and last, words of the phone conversation.

Mason returned to his office area and pulled out the Rosemont papers for another look. He slowly ran his fingers across the seemingly imaginary number on the bottom of the sheet. This was the biggest deal he had done on his own. His father was usually the chief negotiator of the big boy deals, but he had been giving Mason more rope. He still watched Mason like a hawk, no doubt— but from a slightly more distant tree. He knew that, at 63, he was losing his fastball (though his curveball was still fine, he convinced himself). While there was still no confusing who was Furbacher and who was Son, the latter was climbing that ladder.

0 Comments Add a Comment?