Leather Hands and a Generous Heart

It was 2012, a warm Sunday afternoon in the old section of Conshohocken. I was sitting in my grandfather’s (Pop-Pop) living room, or parlor, as he would call it. He was reclining in his well-worn La-Z-boy chair, a throne he no doubt earned after seven decades of being anything but a lazy boy. Two hundred thousand hours of manual labor as a carpenter, bricklayer, roofer and general contractor had finally paid a toll on his body. He was 90 years old and ailing. My grandmother (Mom-Mom) had passed away a year earlier and he was still figuring out life without her.

During the two hours or so that we relaxed and chatted in the parlor that day, the squeak of the screen door was incessant. Sometimes a knock came first, sometimes it just opened. Each time there was a neighbor of my grandfather standing there with an offer or dictate. They came to walk his dog or mow the grass or trim a tree or bring him a meal or ask him if he needed a ride to his next appointment. Some just came to say hi or let him know what was happening in the neighborhood. We visited him once a month or so at that point and each visit had similar neighborly interruptions.

This was when I learned what true social security looked like. And it wasn’t a government program. It was this beautiful and ancient mechanism that the God of creation established for his people. Pop-Pop stumbled upon it. Or, more precisely, he paid into it without giving thought of how it would come back to bless himself. He was a generous man. And, as the etymology of “generous” indicates, he lived open-handed within the concentric rings of “family”-- from the biological family to the community family.

Mom-Mom, a generous woman in her own right, told us stories of her frustration of the numerous times Pop-Pop would come back from a neighborhood job with half the money he should have received from the work. Sometimes he returned with none of it. She knew he was not a frivolous spender and that he didn’t blow the money on the way home. After pressing him further and sometimes investigating on her own, she would be reminded of his internal sliding-scale billing system.

If Pop-Pop showed up to a job and saw evidence of the homeowner or their family struggling in some way, he dropped the price. If he noticed something else needing to be fixed in their home while he was there, he would fix it, sometimes without them knowing. If the homeowner was sick, he would reduce the bill. If the homeowner was a widow, he would sometimes just rip up the bill and sneak out the back door when the work was done. The ladies may have chased his truck down the street with a wad of one dollar bills, but he would feign ignorance and step on the gas.

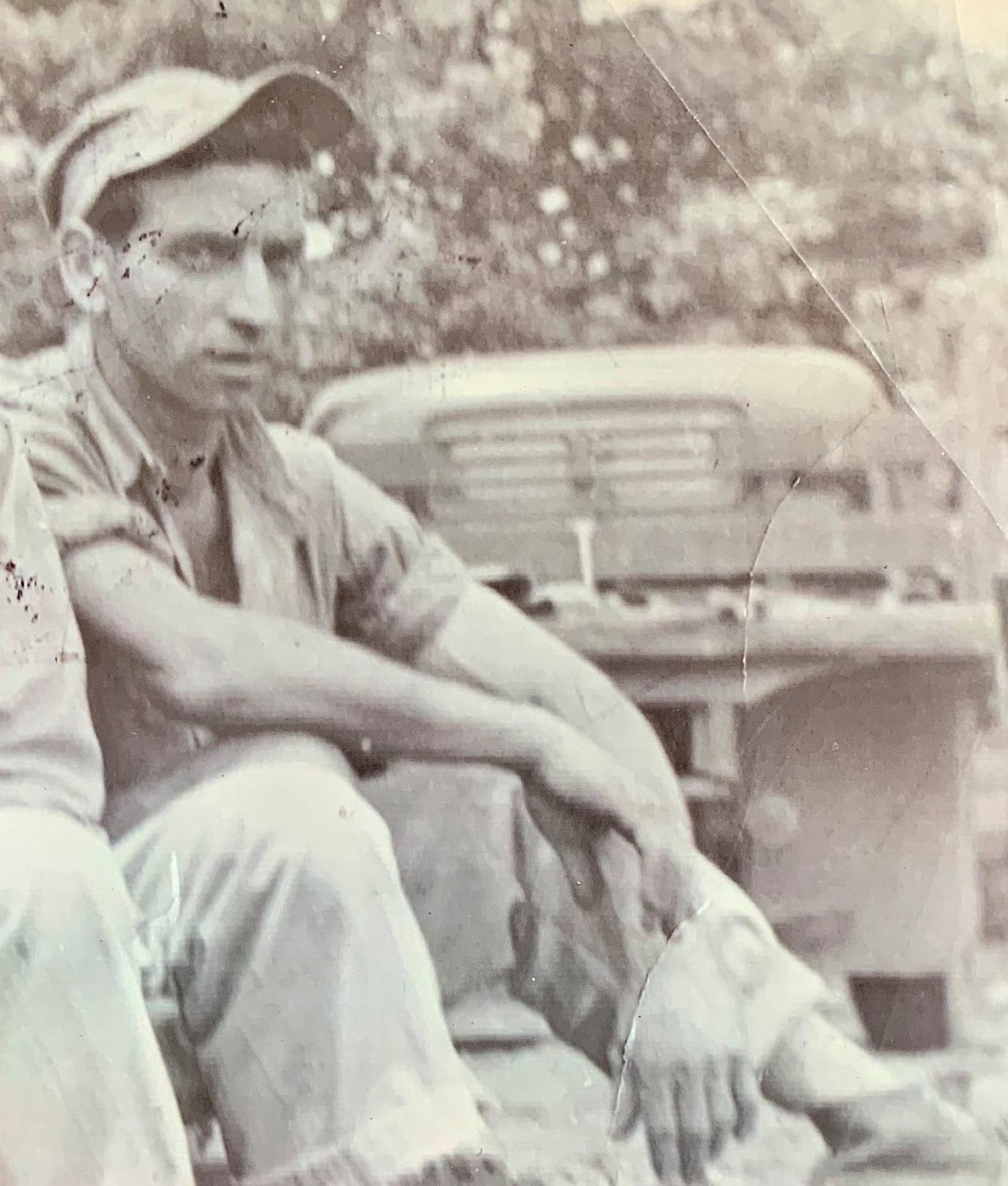

He was generous in other ways, too. I saw it often. I had an early sense of the social credit he earned in his community. I would drive around the streets of Conshohocken with him in his old truck. People on their lawns and sidewalks would smile and wave at him as we passed. He was missing parts of multiple fingers due to some gruesome hammer and saw injuries. So, when he waved back, it looked like he was throwing up a West-Conshy gang sign. Often he would pull over to chat for a while, forgetting we were supposed to be back at the house at a certain time.

I don’t say these things to deify Pop-Pop. He was not perfect. He was a product of his time, his personal family dynamics and his cultural upbringing in a first-generation Italian-American family trying to find their way in a new land. He didn’t always know how to navigate familial situations with sophistication or emotional intelligence. Like the rest of us, he was far from perfect. But he had perfected the giving drivetrain of the gift-gratitude cycle. His primal instincts were to be generous. He gave freely to his biological family and to his community. He had trouble turning a blind eye to a need. It was his nature to share with those less fortunate than he, even if it meant his personal empire would stagnate and never rise above lower-middle class.

Pop-Pop built his 1000-square foot house in Conshohocken 70 years ago with his own hands, back when blue-collar families could afford to live in this Philadelphia suburb and when there were enough woods to go deer hunting. He raised his 4 kids in that little house. He regularly hosted family gatherings of 20+ people in that little house. He was proud of what he produced in that little house, even if it took him until the end of his life to fully recognize it, appreciate it and express it. There were very few updates made to that house that I can remember in the 30 years that I visited. Pop-Pop didn’t have a lot in terms of money or material possessions. But Pop-Pop was rich. He had learned the secret of contentment found in the freedom of giving.

On Sunday March 24, 2013 he passed away in that same house. Two of my kids had gone with my parents to spend time with Pop-Pop that day. When they arrived, they found him dead in the back room. The back room is where the plants and candy lived. I tend to believe Pop-Pop was in that back room to retrieve the candy bin, knowing my kids would be coming soon. It would have been his last charitable act on Earth, as charity isn’t needed in heaven. If he wasn’t giving, he wasn’t being.

Everyone leaves a legacy. In my eyes, Pop-Pop’s legacy was one of generosity. It was a legacy so strong in his community, that in his moments of greatest need at the end of his life, his community enveloped him in care. When his biological family was not available to help him, the neighbors were. It was a beautiful reminder of the power of generosity and the gift-gratitude cycle in a community. Love of neighbor and generosity is each person’s greatest social security, in my opinion. It’s God’s design in nature. It’s the design for man. I’m grateful for this legacy from Pop-Pop, which was passed down to my father and, Lord-willing, I will continue through me.

0 Comments Add a Comment?