The Zephan (Excerpts)

Turning twelve years old is kind of a big deal in Straighthaven. Linnea knows it is, mainly because her father told her so.

“Ready Linnie Minnie?” her father says at the bottom of the stairs.

“Yes!” she said, sliding down the banister, headfirst, with her chin propped up on her mohair sock-gloves. “Do we have time to eat breakfast?”

“Time? Time, you ask?

Time is but sand

In a broken flask.

If you remember anything, honey,

Remember:

Time is money”

She thinks about that for a moment

Because it sounds funny.

Are Seconds just pennies and minutes but dimes

…She wonders,

“Is time ever just time?”

Does the sun punch a clock before it can shine?

Does it work for a dozen then sprint o’er the line?

Linnea finally yields to her father’s funny philosophy. “Okay Father, I will eat as we walk.”

Her father hoists a large burgundy briefcase onto the kitchen counter.

“What’s in it, Father?” she asks with dancing eyebrows.

“You’ll see! You know this is a very important day for you, right?”

She knows, but not really. See, her smile may be steady, but her head isn’t always heady. Too often her thoughts are a swirling eddy of confetti and spaghetti. At least that’s what her father says, the firm lump of gumption he is.

Take for example this great big Sycamore tree with a dinosaur-leg trunk and a dreadlocked crown. The oldest living being in town, with more stories than ole Sarah Teller. Linnea’s eyes light up at the prospects of a tree this grand.

So does Father’s. He reaches into his box and pulls out a black notebook and some kind of multi-measuring device. “Height: 40 meters. Diameter: 1 meter. About 120 years. Low rottage, high knottage. 500 notes, I’d say.”

“500 notes? Why do you say that, Papa?”

“Trust me, 500 for sure,” he answers, as he hangs a giant tag around the lowest limb. “Settled. In the books. Ahh, doesn’t it feel good to put a number on it?”

Linnea thin-grins and reaches for the lowest limb. As she climbs she sings,

“Oh, to be a tree, standing firm and free

Oh to be a great big tree

She lets her leaflets fall, from heights so tall

To cushion creatures as they crawl

She leans herself toward sunny rays,

And when it’s stormy still she stays

She shelters others as they grow.

In no rush, she takes it slow”

“800, 900. Go, go, go!” Father exclaims, paying no attention to Linnea, who continues her son:

“A tangled-wood headdress,

A necklace of leaves.

So, what is free,

If not even a tree”.

She grieves.

And continues.

“Can a tree be forbidden?

No climbing

No hanging

No jumping

No sitting

Or is a tree just for bidding

35

40

45

50

How about 60, no time to be thrifty”

Her father shouts, “No, sweetheart, no! What are you doing? Get down. This tree is worth far too much to be playing around on. Besides, it’s not mine and it’s not yours. Unless you have 500 notes?”

“Of course I don’t. Why would I need 500 notes to climb a tree I climbed just yesterday for free?” Her father has his eyes fixed on something and doesn’t hear her question.

“Well, would you look at that,” he exclaims, quite impressed at the empty lot in front of them.

“There’s nothing there, father. I mean, it’s great for playing ball games and riding bicycles. And dancing and drawing funny faces in the dirt with sticks. But why does it interest you?”

“Oh, Linnea, you think too small. An empty lot is quite a lot, if you put in the thought. This is perfect land for building a new store– or a bank. Yes, a bank!” He picks up a stick and draws out a big square with a big window.

“A bank? Why do we need another bank? We just passed a bank and if we walk a little more we’ll pass another, then another. I could throw a stone in the air and there’s a good chance it would hit a bank.”

“More notes are circulating now, honey. And, after our important work today, there will be even more circulating tomorrow. I’m afraid we need more places to keep them safe.”

Afraid of what?

They’re just numbers.

And safe from what,

She wonders.

In her mind, the more notes the more stress.

“I don’t know, Papa,

Maybe we need less.”

Linnea suddenly starts to wonder about this day. Maybe the special part is still to come? Maybe this is just the business before the real fun. She runs to catch up with her Father, who is hanging a tag on a man playing an eleven-stringed instrument and a woman weaving a willow-branch bread basket.

*********************

As Miss Terry walks in with the birthday cake, a whirlwind of commotion outside the building has the party people running to the windows and out the doors.

“What is it? Oh, heavens, what is it!”, Miss Terry exclaims.

Linnea runs to the window to see for herself.

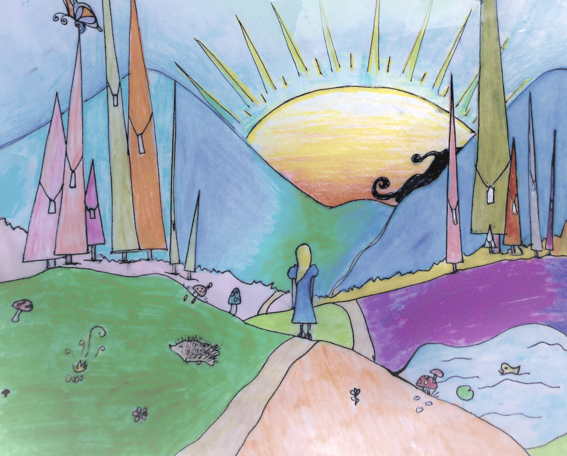

What is it? She feels like she is looking at a wildly abstract painting through the glass. Amid the incongruity, her eyes make out some sort of creature in motion, though she isn’t sure. The dancing colors—blurry yet bright— are hard to ascertain, as if from another world. The creature is seemingly riding on the wind, swirling through the landscape, like a rainbow on fire. Then, as quickly as it had come, it disappears. If it had not paused for a half second, the people may have assumed it was some sort of illusion by the town magicians or a once-in-a-lifetime electromagnetic anomaly. But that split-second, gracious pause was enough for them to conclude that the flash of colors did indeed belong to some manner of living being and not a polychromatic cloud of unknowing. It was not enough time to make out exactly what it was. Did it have feathers or scales? Fur or skin? One lady decides it had all four in abundance.

As the beast vanishes, it leaves a trail of what appears to be a colorful crystalline dust. As this substance rests on the roadside, the nearby flowers seem to perk up in attention. Linnea bends over to see the tigerlilies, nearly dead and naked from the early summer heat just a few minutes ago, now wonderfully dressed again, slow dancing in the breeze.

The adults erupt in a frenzy of discussion, oblivious to the brilliant dust trail.

“What was it? Oh Strange Earth, what was it!” They took turns guessing and disagreeing.

Butch the Barber says, “I must find this beast. How glorious its hair must be, if it indeed has hair! Think of all the beautiful wigs and extensions it would make. More importantly, think of all the notes I would make.”

Barbara the Butcher responds, “I, too, must find this beast. But it will be worth more to me dead than alive. A beast so large, so exotic-- no doubt would have the choicest meat. Twenty, maybe fifty… maybe a hundred notes per pound!” She begins frantically filing her large knife right there on the sidewalk.

“Not a chance. This beast must be kept alive at all costs. Imagine it on exhibit, year-round, right in the middle of the zoo. Think of the attraction it would be. Think of the crowds it would bring from all over the town and even the yonder places. Observer after observer; customer after costumer. And, of course, note after note after note after note after....” Sue the Zookeeper is already drawing out the exhibit in her mind.

The jeweler, believing she saw shiny scales on the beast, envisions the expensive jewelry she could make.

The farmers and foremen fantasize about putting it to work, replacing manpower with beastpower.

The engineers and scientists and medicine-makers all salivate at the unknown prospects

.Linnea walks through the crowd and hears a song break out:

“Furniture from its bones,

Sausage from its loins;

Jackets from its fur

Bills and bills and coins

Wigs from its long hair

Regalia from its scales

Jackets from its fine fur

Sales and sales and sales

Power from its electrons

Power from its fangs

Power from its muscle

Its power in our hands”

Linnea cannot think of how to use the beast for herself. Her mind doesn’t tend to bend that way. But she is curious about the beast nonetheless. She notices the same butterfly from earlier resting in the middle of the road. It is an odd and dangerous place for such a delicate creature to rest. She walks toward it, hoping to stir it back up into the safety of the air. It flies about ten meters and then rests in the road again. As she approaches again, it flies another ten meters and lands back in the middle of the road.

“Mister Butterfly,

or maybe you’re a Madame,

I’m only trying to keep you

off of the macadam.”

She continues to follow the butterfly until she lost track of time and place. Before she knows it she is out of Center Square and off Market Street. She had turned onto Broad Street. The butterfly had led her from the macadam to the cobblestone to the loose stone, all the way to where the road narrowed into a dirt path, which faded into the woods.

0 Comments Add a Comment?